|

“Full

of Confidence” The American Attack

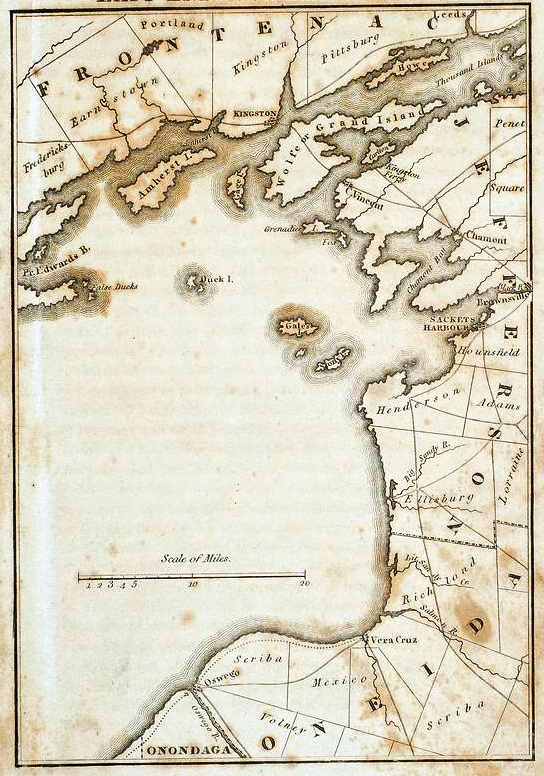

A cold westerly wind coming off the lake chilled the American sailors as they hoisted the sails on seven armed vessels at Sackets Harbor, New York on November 9, 1812. All was in a bustle. Supply barrels were rolled on board, artillery pieces were loaded, marines stowed their knapsacks, and midshipmen called out orders through brass speaking trumpets to seamen on the masts above. Arriving in early October,[1] U.S. Commodore Isaac Chauncey was now ready to put his little fleet to the test and challenge Canadian control of Lake Ontario. An attack on Kingston, Upper Canada was also “in the wind”[2] if a decisive naval victory could be achieved. The first five months of the war in the Great Lakes region had been a disaster for the United States. Detroit had been captured and in October 1812, the American invasion of the Niagara peninsula was foiled on the heights overlooking Queenston and the enemy had taken Fort Mackinac. Since the declaration of war in June, command of Lake Ontario, and indeed of all the lakes, had rested firmly in the hands of the British inland naval service known as the Provincial Marine. Without the Royal Navy on the lakes, the Provincial Marine had been created in the 1778 to provide an inland water transportation service. While sailing in armed vessels, the principal job of this service was to transport goods and personnel back and forth across Lakes Ontario and Erie. Officers of the Provincial Marine had no military experience and were more like merchantmen hired by the army’s quarter master general’s department to perform a forwarding service. Lake Ontario’s flagship of the Provincial Marine was the Royal George. Built in 1809 at Kingston, the Royal George was a 96 feet long vessel armed with twenty-two 32-pounder(pdr) carronades. A carronade was a short-barrelled artillery piece that was much lighter than traditional long guns, which was ideal for dose-range actions, but which was less accurate at longer ranges. Reducing weight was important to improve a vessel’s speed and avoid making it top heavy. In addition the short carronades required less crew to operate them. By contrast, the largest American ship under Chauncey’s command, the US Brig Oneida, was armed only with sixteen 24-pdr carronades.[3]

What the Americans lacked in firepower they made up in skill. One sailor on the Oneida pointed out that while the Royal George “was big enough to eat us” the ship’s “officers, however, did not belong to the Royal Navy.”[4] Master and Commander of the Royal George was Commodore Hugh Earle. While Earle had served in the Provincial Marine on-and-off since 1792, he was inept at the proper management of a war vessel. His superior officer noted Earle’s “conduct as an officer has been much and justly censored for want of spirit and energy … in the discipline and interior economy of his ship.”[5] Earle’s lack of attention was reflected in the state of his vessel and crew. An inspecting officer found “the general appearance of the men” exhibited “the greatest want of attention to cleanliness, and good order” and the ship was “in the most filthy [of] condition.” When the carronades were fired during this inspection “the greater part of them missed fire repeatedly in consequence of the vents being choked up and would not go off till they were cleaned out with the pricking needles and fresh primed.”[6] Worse still was the lack of seamen on board. Only seventeen were listed as such, out of a complement of 80 men. [7] Of that number only eight were considered “able” seamen.[8] Not so for the Americans. Commodore Chauncey, the newly appointed commander of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, arrived at Sackets Harbor with a parade of experienced sailors from the Atlantic coast to man his ships. Chauncey himself had fought in the First Barbary War in 1804 and had most recently commanded the naval yard at New York. Chauncey’s second-in-command and the commander of the Oneida was Lieutenant Melanchthon T. Woolsey, who had been in the U.S. Navy since 1800 and he knew Lake Ontario well. Stationed on the lake since 1808, Woolsey had supervised the building of the Oneida in 1809 and had outfitted six schooners with guns prior to Chauncey’s arrival. After only a month in his position, Chauncey was ready to battle Earle for control of the lake.

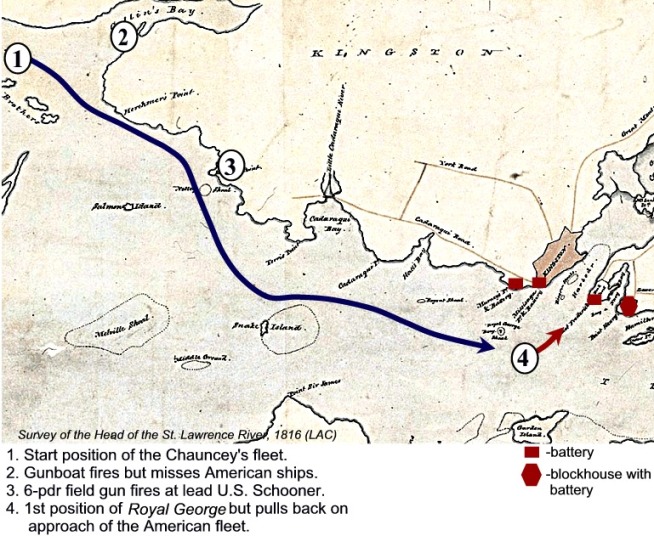

Writing to the Secretary of the Navy, the commodore outlined his plan: “As I have reason to believe that the [Canadian ships] Royal George, Prince Regent, and Duke of Gloucester have gone up the Lake with troops to reinforce Fort George [on the Niagara peninsula]” and expecting them to return to Kingston “I have determined to proceed with the force I have ready in quest of the enemy.” Chauncey decided that the best place to lay a trap was near the False Duck Islands in the middle of the Eastern part of Lake Ontario “where the enemy are obliged to pass.” In his letter he also stated that he would “make an attack upon Kingston for the purpose of destroying the guns and public stores at that station” only “if I should succeed in my enterprise.”[9] By noon of November 9, Chauncey’s seven vessels were in position waiting for their prey. Towards the end of the afternoon with the sun setting, the Royal George finally appeared. Ned Myers, an American sailor, recounted: “we made such a show of schooners, that though [the Royal George] had herself a vessel or two in company, she did not choose to wait for us.”[10] Chauncey immediately gave chase forcing the Royal George into the Bay of Quinte but soon lost sight of her in the darkness.[11] Knowing the local waters well, the Royal George slipped through the gap[12] and into the North Channel. During the Royal George’s escape there was no exchange of fire.[13] Because Chauncey’s fleet lost sight of the Royal George in the darkness while still in the Bay of Quinte, and not chancing to run around in the night trying to navigate unknown waters, they would have anchored. In addition it was standard naval practice to anchor well away from enemy shores to safeguard from a surprise attack.[14] In the meantime, the Royal George continued slowly eastward along the lake’s north shore, eventually arriving at Kingston at 2 am.[15]

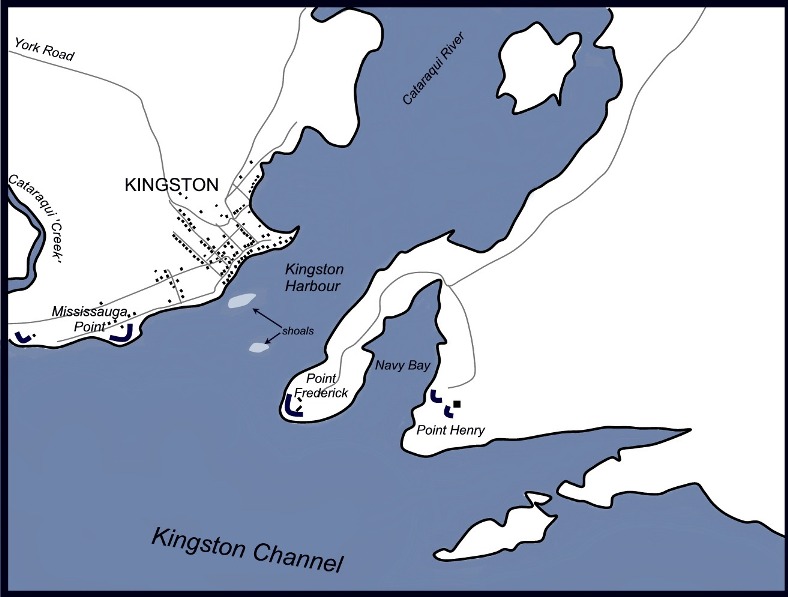

Earle immediately informed the commander at Kingston, Lieutenant-Colonel John Vincent that Chauncey had taken to the lake and may attack Kingston.[16] One witness recounted: “In a moment every person was under arms, detachments were sent to the different bridges over Cataraqui creek, each attended by a field piece, and every other necessary precaution taken with the greatest alertness.”[17] Kingston’s local newspaper reported “the alarm had been early communicated through the country, and persons of every age flocked into town from every quarter” of Midland District.[18] This would have included the militias from the nearest counties of Frontenac, Lennox, and Addington.[19] Being the beginning of the war, the true loyalties of the District’s residents were by no means certain to British officials because of the number of recent American immigrants living in the area. However to Vincent’s relief, Canadians answered the call: “the conduct of the inhabitants of the Midland District on this occasion will be long remembered to their honor.”[20] The flood of local volunteers proved to be somewhat problematic for Vincent because Kingston’s ordnance stores lacked enough small arms to equip them. Many simply milled about the town without any tasks assigned to them. [21] While the artillery mounted at points Mississauga, Frederick and Henry protecting Kingston’s harbour was insufficient, the town had a sizable garrison of British troops. There were over two hundred men of the 49th Regiment of Foot and a detachment of a hundred seasoned soldiers of the 10th Royal Veterans to challenge any enemy attack. Also the Royal Newfoundland Fencibles had over a hundred men stationed in Kingston to serve as marines on the Provincial Marine vessels. [22]

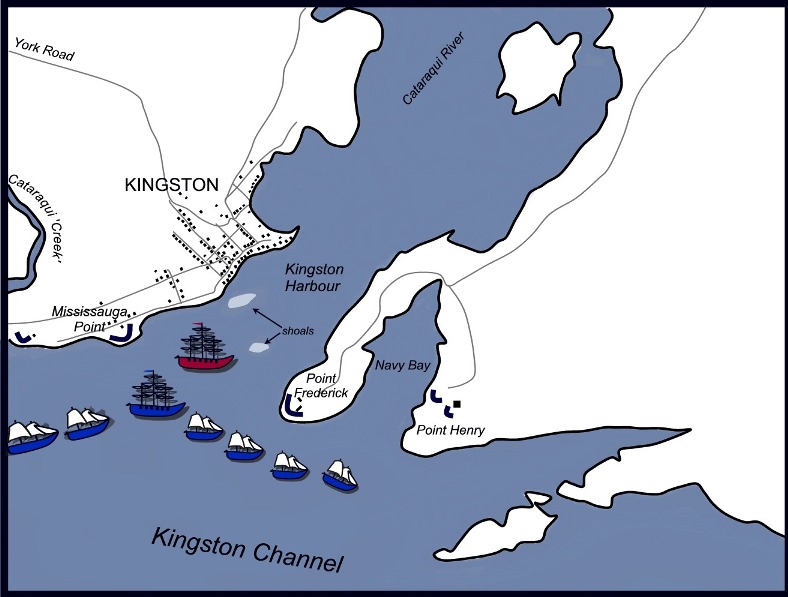

The following morning at sunrise, Chauncey’s fleet weighed anchor and set sail in search of the Royal George. Passing through the gap unopposed, the Commodore caught sight of a merchant schooner anchored at Ernestown (modern Bath) and dispatched a boat to take possession of it. The capturing of any vessel was fair game for naval forces on both sides. Seizing of ships not only denied the enemy of craft that could be armed, but it provided profit to the seamen in the form of “prize money” when the captured goods were sold at public auction. As a result, hundreds of schooners were captured and recaptured throughout the war.[23] As an example, only a month earlier the Royal George had herself seized both the American merchant schooner Lady Murray and a small US Revenue Durham boat at the village of Charlotte, N.Y. [24] According to two witnesses, Chauncey “sent a flag of truce on shore demanding a schooner belonging to Benjamin Fairfield…threatening in case of refusal to destroy” the village.[25] The schooner, named the Two Brothers, was promptly turned over to the Americans without resistance and the American visitors set sail to join Chauncey’s force.[26] Thinking the captured schooner “would detain us”,[27] Chauncey ordered Lt. Joseph Macpherson to remove the sails and rigging of the Two Brothers and burn the vessel. This occurred somewhere between Ernestown and Collin’s bay; the US vessels Hamilton and Governor Tompkins were assigned to this duty.[28] Sometime just after 1pm, near Collin’s Bay, Chauncey caught sight of the Royal George anchored in Kingston Channel,[29] under the protection of the harbour batteries (near Garden Island).[30] British Colonel John Vincent confirms this by remarking that Commodore Earle “did not think his force sufficient as a match for the fleet against him, and placed his vessel between our batteries.”[31] While troops in Kingston thought the Americans were an invasion force, Chauncey was focused only on the taking of the Royal George and signalled his fleet to attack.[32] Seaman Myers briefly recounted what happened next: “we ran down into the bay, and engaged the ship and batteries, as close as we could well get.”[33] As Myer’s ship the Oneida followed the four faster schooners towards their target, a junior officer onboard remembered that the ship’s commander

Ineffective fire from a British gunboat in Collin’s Bay greeted the tiny American fleet to the Kingston area, which was returned but also “without effect”.[35] A light brass 6-pdr artillery piece, unlimbered on Everett Point - five miles west of Kingston - was next to try and inflict some damage on the lead schooner Conquest, under the able command of Lieutenant Jesse Elliot. Royal Artillery Lieutenant George Charlton[36] claimed that he fired “a load of grape shot about the decks and rigging of their foremost schooner.” Charlton thought the Conquest’s rigging was so damaged that “she, after firing 2 or 3 shots from a 32 pounder, tamely sheered off towards Snake Island.”[37] Considering the subsequent manoeuvres of the schooner, it is more likely the Conquest was leading the vessels following it away from shore and out of range of Charlton’s field gun. A detailed American report later stated that the Conquest received no rigging damage.

Now positioned in the mouth of Kingston harbour, Earle likely thought, ‘Surely the Americans would not dare engage him while the Royal George was under the protection of the artillery on shore.’[40] He was wrong. The American vessels sailed past, firing at their target and the batteries. The four lead vessels passed Kingston harbour and turned back for another run at the Royal George. While turning, these smaller vessels of Chauncey’s fleet came within range of the two batteries on Point Henry. Directing the gunners on Point Henry was 58-year-old Lieutenant Francois Tito Lelievre of the Royal Newfoundland Fencibles. [41] Lelievre was not unfamiliar to naval warfare, having been in the French navy when the royalist fleet defected to the British at Toulon in 1793.[42] However, the combination of the small calibre of his artillery pieces and his distance from the enemy frustrated Lelievre’s best efforts to inflict significant harm. Indeed, the collective fire of all the eastern shore batteries failed to dampen the American desire to “cut out” the Royal George. While the lead vessels turned, the Brig Oneida engaged the batteries and Royal George. During this, American seaman Thomas Garnet “was laughing heartily, and, in that act, was cut in two by a nine pound shot.” His officer wrote: “I afterwards saw his countenance; it seemed as if the smile had not yet left it. This disaster only exasperated our seamen, they prayed and entreated to be laid close aboard the Royal George only 5 minutes ‘just to revenge Garnet’s death.’” Facing an undeterred enemy and taking considerable damage from constant fire of the Brig Oneida, Earle appeared to panic. He raised anchor and fell back towards the docks of the town of Kingston. Chauncey responded at 3:22pm by signalling his fleet to “engage closer”, trying to get within boarding range of the prize he so desperately wanted. Seaman Ned Myers on the Oneida remembered: “I was stationed at a gun… and was too busy to see much; but I know we kept our piece speaking as fast as we could for a bit. We drove the Royal George from a second anchorage, quite up to a berth abreast of the town.”

Prior to attacking, Chauncey “directed the squadron to level their fire as much as possible against the ship and forts, as it was not his wish to injure individuals by beating down the houses of Kingston.”[43] Still with Kingston as the Royal George’s backdrop, missed American round shot crashed into the local buildings. Myers adds: “We gave her nothing but round-shot from our gun, and these we gave with all our hearts. Whenever we noticed the shore, a stand of grape was added.”[44] As ranges reduced, U.S. Marines on board the American warships began exchanging musket fire with the Royal Newfoundland Fencibles on the deck of the Royal George and the British infantry on shore. Desperate to counter possible American boarding parties, Earle constantly called to shore for more troops to come on board. One American officer recounted: “The Royal George was so afraid of being boarded by us, that she gave repeated signals for fresh supply of men, and received 2 boats full during the action – her tops were crowded with men.” By contrast the same officer described Lieutenant Woolsey commanding the Oneida as “cool, brave and gallant as Nelson.” [45] Among the men crowded on the decks of the Royal George was Lieutenant Thomas Ridout of the Commissariat. He had boarded the ship earlier in the day to visit his brother John who was a midshipman. Now he found himself in the middle of a battle. Luckily, Ridout had also brought with him a musket that had been given him as a gift.[46]

While the accounts of the fighting leave the impression of a heated engagement, only Private John Sammon, a Danish recruit in the Royal Newfoundland Fencible Regiment, was killed in the exchange. No British or Canadian wounded were reported.[49] During this, tragedy struck one of Chauncey’s vessels. The iron 32-pdr gun of the Pert exploded, badly wounding the vessel’s commander, Sailing Master Arundel, and slightly injuring four others. Refusing to leave his post, Arundel was knocked over board by the boom and drowned while the schooner withdrew from combat. At one point, Royal Artillery Lieutenant Charlton with the 6-pdr field piece arrived and joined the defence effort. At 4pm an American officer noted: “The squadron is now exposed to the cross fire of five batteries, of flying artillery, of the ship with springs on her cables so as to enable her to bring her guns to bear … Showers of round and grape fell around us.”[50] Myers noted “one shot came in not far from my gun, and scattered lots of cat-tails, breaking in the hammock-cloths.”[51] Surprisingly no others would be injured in the affair. The small-calibre artillery on the batteries to much of the blame: “It is to be lamented, that the Guns we have here are only nine pounders, and the enemy kept at too great a distance.”[52]

In the events of the day, the Canadian schooner Mary Hatt had been captured at the mouth of Kingston harbour and was taken in tow as a consolation prize.[53] With the winds picking up from the south-west and night fast approaching, Chauncey signalled for his brave little fleet to withdraw. A boy in Kingston’s dockyards described the view of Chauncey’s ships leaving as “black-winged like bats against the red-striped western sky.”[54] Spirits were high among the American crews. Seaman Myers assessed: “We had the best of it, so far as I could see; and I think, if the weather had not compelled us to haul off something serious might have been done. As it was we beat out with flying colours.”[55] After sailing for two miles (3.2 km) and manoeuvring out of sight of Kingston by taking up position behind Four Mile Point on Gage’s Island, the fleet anchored. While his vessels rocked in the breeze, Chauncey assessed the state of his command. Only Garnet and Arundel had been killed and another eight were slightly wounded. The vessels themselves had received the following damage:

With only minor damage to his ships, Chauncey was determined to make another attempt at the Royal George the following day. However, Mother Nature had different plans. Heavy gales and rough waters made another attack impossible.[57] Chauncey considered his options and a plan was devised to try and coax the Royal George out. Accordingly, the American vessel Growler, with the captured schooner Mary Hatt, sailed past the mouth of Kingston harbour and down the eastern channel. Preoccupied with repairs, the Royal George chose not take the bait.[58] However the day brought with Chauncey a different opportunity. On its way back from Niagara, the Provincial Marine schooner Simcoe appeared on the horizon. Its commander, Kingston- born Lieutenant James Richardson[59] was caught completely unaware that Chauncey was now in command of the lake. American vessels Governor Tompkins, Julia and Hamilton immediately gave chase. [60] Twenty-two year-old Richardson initially considered running his schooner aground on Amherst Island but the winds had baffled this plan. The Americans closed and then opened fire on the Simcoe but one attacking vessel “missed stays” in the strong wind, or failed to get the ship’s bow up enough to come about. Richardson apparently mocked the mistake to his crew shouting: “Look, lads, at these lubbers! Stand by me, and we will run past the whole of them, and get safe into port.”[61] Richardson’s vessel was forced to run a gauntlet of American vessels that mauled her so much with grape and round shot that “all her people run below while under the fire.”[62] Unarmed, the Simcoe pressed on desperate to reach the safety of Kingston harbour. Just when the crew thought they may get through, a 32-pdr shot crashed through the hull and the schooner began to take on water. Unable to make the harbour, Richardson directed the vessel straight for shore, west of Kingston. The Hamilton continued in hot pursuit after her. As the Simcoe neared shore, a British field gun moved in unison, and stopped near Everett’s point to give covering fire. Sergeant James Canniff of the Addington Militia, still guarding the western approach to Kingston, witnessed the event from Herkimer’s Nose. The Simcoe was described by the Americans as “escaping over a reef of rocks” (likely Nettey Shoal off Everett’s Point) and sunk in nine feet of water next to the shore.[63] As the Hamilton neared, the Royal Artillery’s brass 6-pdr gun open fired. At this point, the American vessel had little choice but to veer off and give up the chase. Apparently, the local militia witnessing the event from the shore let out a cheer at the American withdraw.[64]

A few days later, Chauncey captured the Sloop Elizabeth further out in the lake, before returning to Sackets Harbor.[65] Captured on the latter vessel was Captain James Brock, paymaster of the 49th Regiment of Foot and first cousin to the late Major General Sir Isaac Brock. James was returning with the worldly possessions of his cousin when the Elizabeth fell into American hands. The proper procedure in handling captured goods was to auction them off and distribute the earnings to the officers, marines and sailors involved in their capture. Called prize money, it was a major motivation for joining the navy. However, in respect to the late enemy general, every man entitled to prize money from the sale Isaac Brock’s belongings waved his right. Chauncey granted James Brock his parole and he was free to return to Upper Canada with the cousin’s baggage.[66] One cannot help but admire the noble gesture made by the American seamen under Chauncey’s command. When James Brock arrived back in Kingston, he reported to military officials that Chauncey was “full of confidence in his strength.”[67] He had every right to be. The Provincial Marine had shown they were not an effective naval fighting force. Indeed, the officer overseeing them was quite blunt when he wrote to the governor and commander-in-chief of British North America, Lieutenant-General Sir George Prevost: “On Lake Ontario the good of the service calls for a radical change in all the officers [his emphasis] as I do not conceive there is one man of this division fit to command a ship of war.”[68] Kingston society appeared to agree. Because of their less than stellar performance in Kingston harbour, the members of the Provincial Marine had become almost social outcasts. One officer wrote: “the officers of the marine appear to be destitute of all energy and spirit, and are sunk into contempt in the eyes of all who know them.”[69] Only what could be described as ‘doom and gloom’ gripped British military officials. Lieutenant Governor and commander of Upper Canada, Major-General Roger Sheaffe warned Prevost: “the enemy is preparing the most formidable means for establishing a superiority on the lakes.”[70] Only days after Chauncey’s visit to Kingston harbour, the Executive Council of Upper Canada described the American control of Lake Ontario as “distressing” adding: “by land our success has exceeded our hopes – not so is our warfare on the lakes.”[71] With the launch of another enemy warship in late November, Kingston officials expected their naval establishment to be wiped out by Chauncey in the coming days: “the efforts of the enemy are such that nothing can save our navy from destruction.”[72] To the relief of Upper Canadians, once again Mother Nature intervened to foil Chauncey’s plans. In late November, Chauncey reported being forced from the lake by frigid temperatures and snow. Three days of heavy snow made roads to Chauncey’s naval base at Sackets Harbor almost impassable: “winter in this quarter appears fairly set in.”[73] The early onset of winter also changed British naval plans on Lake Ontario. Prior to the war, York (Toronto) had been chosen over Kingston as the winter naval base for the Provincial Marine and steps had commenced to transfer the dockyard facility to the provincial capital. Since Kingston’s navy harbour froze in winter exposing military vessels to attack, military officials thought York was the better choice, which was further removed from the United States.[74] However, the bad weather forced the Provincial Marine squadron to be split between Kingston and York for the winter.[75]

Chauncey’s attack on Kingston harbour was a minor skirmish, but it had important strategic consequences. Casualties in the affair were light the garrison at Kingston had successfully protected the Royal George from being snatched away but the Americans were not deterred from trying again. The harbour defences were feeble and Provincial Marine personnel were inexperienced and unsteady and in the new year, steps would be taken to improve both. The attack on Kingston left Chauncey with undisputed control of the lake and gave the United States its only important success since the war began. For that reason, the Americans could claim victory. However, there were positive results for the British. Up to this point, military officials were uncertain how many residents of Midland District would answer the call to arms. Significant numbers of American immigrants had recently populated the area and signs of sympathy for the United States had been shown in some communities between Kingston and York. Therefore any questions about Kingston area’s loyalty were put to rest on November 10, 1812.[76] The affair also shone light on a glaring weakness in the British defence strategy for Upper Canada leaving Prevost to request the assignment of the Royal Navy to the inland waters of North America. The US Navy had taken Lake Ontario by storm and only the professional sailors of the Royal Navy were capable of answering that challenge.

Acknowledgements I would like to thank Major John Grodzinski of Royal Military College for reviewing my findings and for making a number of helpful suggestions. - Robert Henderson [1] Chauncey to Hamilton, Sackets Harbor, October 8, 1812 published in William Dudley ed., The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. (Washington, 1985) p. 336. [2] J. Fenimore Cooper, ed. Ned Myers; or A Life Before the Mast. Vol. 1 (London, 1843) p. 111. [3] See Robert Malcomson, Warships of the Great Lakes, 1754-1834. (Kent, 2001) [4] Cooper, Ned Myers p.113. [5] Library and Archives Canada (LAC), Record Group (RG) 8 I, vol. 729, p. 119. Gray to Prevost, Kingston, March 12, 1813. [6] LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 729, p. 28 Gray to Vincent, Point Frederick, January 16, 1813. [7] LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 728, p. 135. Gray to Prevost, Kingston, December 3, 1812. [8] LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 731, p. 43-45. List of Officers and Seamen on board the Royal George, October 2, 1812. [9] Chauncey to Hamilton, Sackets Harbor, November 6, 1812 published in H.Niles, ed. The Weekly Register. Vol. III (Baltimore, 1813) p. 206. [10] Cooper, Ned Myers p.113. [11] Chauncey to Secretary of the Navy Hamilton, Sackets Harbor, November 13, 1812 published in H.A. Fay, Collection of the Official Accounts in Detail of all the Battles Fought by Sea and Land. (New York, 1817) p. 42. [12] The “gap” is the area between Amherst Island and Prince Edward County. [13] Ned Myers specifically states that the first shots he saw fired in anger were in Kingston harbour the following day. Cooper, Ned Myers p.114. [14] Anchoring close to shore exposes your vessel both to enemy fire and surprise boarding by boat. Finding the gap at night and then entering and anchoring in the North Channel is not consistent with naval logic of the time and seems unlikely. [15] Extract of a letter written by a young Gentleman at Kingston, November 20, 1812 published in the Quebec Mercury December 3, 1812. [16] It is likely Vincent had heard the rumour from Sackets Harbor that Chauncey may attack Kingston. Information flowed freely across the border in both directions. Earle’s intelligence seemed to have confirmed Vincent’s fear. [17] Extract of a letter… Quebec Mercury December 3, 1812. [18] Kingston Gazette. November 17, 1812. [19] Drawing the district’s militias in to protect the main military post was a typical procedure. For example, when Prescott was threatened by an American force in November 1813, Brockville’s militia (21km away) was ordered to its defence. This left Brockville defenceless while thousands of US troops past by the town by boat on the St. Lawrence River. See Donald E. Graves, Field of Glory: The Battle of Crysler’s Farm, 1813. (Toronto, 1998). [20] Kingston Gazette. November 17, 1812. [21] Kingston Gazette. November 17, 1812. [22] LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 1707, p. 56, Weekly Troop Distributions, Upper Canada, November 25, 1812. [23] For example, a privateer schooner called the Liverpool Packet out of Nova Scotia captured a total of 50 American vessels. [24] LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 731 p. 42-43. Memorial of Hugh Earle for prize money. Kingston, October 15, 1813. Ships taken on October 2, 1812. Ironically the Lady Murray would be recaptured by the Americans in June 1813. Benson J. Lossing, Harpers’ Popular Cyclopaedia of United States History. Vol. 1 (New York, 1881) p. 759. [25] Statement of John George and Peter Davy. Bath, February 1824. LAC, RG 19 E5-A File 2 Broad of Claims for War of 1812 Losses. [26] Local legend suggests the Addington militia and the 89th Regiment of Foot resisted the American seizure. This is false. The Addington militia had been ordered to Kingston and the 89th Regiment of Foot would not arrive in Canada until the following year. There is no evidence that any shots were fired at anytime while Chauncey’s fleet was in the North Channel. Returns show no British regulars stationed anywhere along the North Channel. LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 1707, p.56. Weekly Troop Distributions in Upper Canada, November 25, 1812. [27] Presumably the schooner would slow the fleet. Chauncey to Hamilton, Sackets Harbor, November 13, 1812. published in William Dudley ed., The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. (Washington, 1985) p. 345. [28] An American officer noted the Hamilton and Governor Tompkins were “far astern having been dispatched in the early part of the day on particular business.” Extracts of letters from an officer under Commodore Chauncey. American and Commercial Daily Advertiser, December 1, 1812. Pairing up the two schooners would have been a prudent move, considering other Provincial Marine vessels were out somewhere on the lake. [29] Channels and waterways were specifically named and defined on nautical maps from the time. Historically the Kingston Channel began where the Greater Cataraqui River joins the St. Lawrence and headed east to the end of Howe Island. See LAC, Map Collection. NMC11288. “Index to the survey of the Head of the River Saint Lawrence made by order of the Right Honorable The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty in the year 1816 under the Direction of Captain Wm Fitz. Wm. Owen R.N.” [30] US Lieutenant Jesse D. Elliot noted the Royal George “riding in Kingston Channel, under the protection of the English batteries.” Plattsburgh Republican. March 28, 1833. There were only two batteries west of the Greater Cataraqui River, one at Murney point and the other at Mississauga point (sometimes referred to as Indian or Messilangoe point) Quebec Mercury December 3, 1812. [31] “Between our batteries” refers to between the battery at Mississauga point on the west side of the mouth of the Cataraqui River and the battery at Point Frederick on the east side. LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 228, p.80 Vincent to Sheaffe, Kingston, November 11, 1812. [32] Col. Vincent agreed noting “I must suppose their visit was only intended to cut out the Royal George.” LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 228, p.80 Vincent to Sheaffe, Kingston, November 11, 1812. [33] Cooper, Ned Myers p.113. [34] American and Commerical Daily Advertiser, December 1, 1812. [35] Kingston Gazette. November 17, 1812. According to Seaman Myers from the time the US fleet set sail from Sackets Harbor to that point no shots had been fired. Cooper, Ned Myers p.113 [36] National Archives, UK War Office (WO) 10/96 Muster rolls of the Caddy’s Company, 4th Battalion, Royal Artillery. April, 1813; Extract of a letter… Quebec Mercury December 3, 1812. [37] Extract of a letter… Quebec Mercury December 3, 1812. The US Schooner Conquest did have one 32-pdr long gun, along with one 24-pdr, and two 9-pdrs. Previously a merchant craft, the small vessel was crewed by 35 seamen, not including officers and marines. Geneva Gazette. December 9, 1812. [38] LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 728, p. 137 Gray to Prevost, Kingston, December 3, 1812. [39] LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 1707, p. 56. Weekly return of troops in Upper Canada, November 25, 1812. [40] This assumption is based on Vincent’s comment that Earle did not want to venture out beyond the protection of the harbour’s batteries. LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 228, p.80 Vincent to Sheaffe, Kingston, November 11, 1812. [41] National Archives (NA), UK, War Office 25/765, p. 132-3, Service Record of Francis Tito LeLievre. [42] LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 548, p.54, Memorial of Francois Tito Lelievre, Quebec, March 3, 1808. [43] Account of American Naval Officer. Norfolk and Portsmouth Herald, December 5, 1812 [44] Cooper, Ned Myers p.113-114 [45] Account of American Naval Officer. Norfolk and Portsmouth Herald, December 5, 1812 [46] Matilda Edgar, Ten Years of Upper Canada in Peace and War, 1805–1815 Being the Ridout Letters. (Toronto, 1890), p. 167. [47] Laurie Stanley “MacPherson, Donald” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. [48] Chauncey to Hamilton, Sackets Harbor, November 13, 1812 published in William Dudley ed., The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. (Washington, 1985) p. 348. [49] NA, UK, WO25/2206 p. 38 Casualty Lists, Royal Newfoundland Fencibles, November 1812. It was rumoured in Sackets Harbor that he was sick in his hammock below decks when he was killed by an enemy round shot that penetrated the hull. [50] Account of American Naval Officer. Norfolk and Portsmouth Herald, December 5, 1812. [51] Cooper, Ned Myers p.114. [52] LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 228, p. 80. Vincent to Sheaffe, Kingston, November 11, 1812. [53] Chauncey to Hamilton, Sackets Harbor, November 13, 1812 published in William Dudley ed., The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. (Washington, 1985) p. 345. [54] C.H.J. Snider, In the Wake of the Eighteen-Twelvers. (Toronto, 1913) p. 26. [55] Cooper, Ned Myers p.114. [56] Chauncey to Hamilton, Sackets Harbor, November 17, 1812 published in William Dudley ed., The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. (Washington, 1985) p. 350. [57] William Dudley ed., The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. (Washington, 1985) p. 345. [58] Ernest Cruikshank, The Documentary History of the Campaign Upon the Niagara Frontier in the Year 1812. Part IV. (Welland, 1901) p. 209. [59] Richardson later became a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy and lost an arm at the taking of Oswego in 1814. After the war he became a Methodist minister. [60] Chauncey to Hamilton, Sackets Harbor, November 13, 1812 published in William Dudley ed., The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. (Washington, 1985) p. 348. [61] William F. Coffin, 1812: The War, and Its Moral: A Canadian Chronicle. (Montreal, 1864) p. 70. [62] Chauncey to Hamilton, Sackets Harbor, November 13, 1812 published in William Dudley ed., The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. (Washington, 1985) p. 348. [63] Ibid. [64] William F. Coffin, 1812: The War, and Its Moral: A Canadian Chronicle. (Montreal, 1864) p. 71. [65] Captured by the Growler. [66] “Genuine character of American Sailors” The Geneva Gazette. December 30, 1812. [67] LAC, RG 8 I, vol. 728, p.137. Gray to Prevost, Kingston, December 3, 1812. [68] LAC RG 8 I, vol. 729, p. 118. Gray to Prevost, Kingston, March 12, 1813. [69] LAC RG 8 I, vol. 728, p. 135. Gray to Prevost, Kingston, December 3, 1812. [70] LAC RG 8 I, vol. 728, p. 115. Sheaffe to Prevost, Fort George, November 23, 1812. [71] LAC RG 8 I, vol. 728, p. 113-114. Committee of the Executive Council of Upper Canada to Sheaffe, November 17, 1812. [72] LAC RG 8 I, vol. 728, p. 135. Gray to Prevost, Kingston, December 3, 1812. [73] Chauncey to Hamilton, Sackets Harbor, November 21, 1812 published in William Dudley ed., The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. (Washington, 1985) p. 352. This same storm front hampered the American night time attack of Canadian positions on the Lacolle River in Lower Canada. [74]LAC RG 8 I, vol. 728, p. 94. Gray to Prevost, Kingston, November 30, 1812. [75]LAC RG 8 I, vol. 728, p. 140-141. Gray to Prevost, Kingston, December 3, 1812. [76]There were still numerous American sympathizers in the area, and suspicions of disloyalty plagued Kingston. For example William Johnson, who had married an American, was constantly accused of treason. On November 11, 1812 he was falsely accused of visiting Chauncey’s fleet while it was anchored the previous night and William was thrown into Kingston’s gaol. “Autobiography of William Johnson” The Sun, December 28, 1838.

|

||||||||||||||||

Copyright: Access Heritage Inc 2019

Copyright: Unless otherwise noted, all information, images, data contained within this website is protected by copyright under international law. Any unauthorized use of material contained here is strictly forbidden. All rights reserved.

.