|

A 150-year struggle, championed by a

Canadian premier, a women's rights activist and generations

of Canadian veterans, that encountered many hurtles including

the sinking of the TITANTIC.

"The

ship’s aground!” a voice cried out in the darkness as the

transport Harpooner struck a rock off Newfoundland.

Momentarily freed by the raging sea, the vessel smashed into

another jagged protrusion. Taking on water and collapsing on

its side, panic spread through the ship. Fire broke out adding

to the mayhem. Crashing waves washed the life boats, and those

trying to get to them, from the deck. Its masts gone, the

wooden ship slid off the reef and into deeper waters.

A handful of

sailors who had made it to shore, stared helplessly at those

trapped on the floundering vessel. Desperate for an escape

route, a plan was hatched to get a rope from the doomed ship to

the men on shore. Tying the life line around the waist of a

dog, man’s best friend braved the tossing, frigid waters to dry

land. Soon people entered the tumultuous sea holding

desperately to the rope. Debris tossing in the surf, stuck some

ending their hopes of surviving.

Thirty souls

had been pulled from the sea when disaster struck. The rope

caught the razor edge of a rock and was cut. With no means to

replace it, the survivors watched heartbrokenly as the vessel

was torn apart. The “cries and last agonizing sobs of men,

women and children” could be heard above the rolling waves, as

the sea claimed their lives. All told over two hundred War of

1812 veterans with their wives and children were lost that day

on November 10, 1816.

Today another

ship seems to have crashed on the rocks and is taking on water

fast. Canadian awareness of their historical roots was

sinking. A generation ago, it was a given that the War of 1812

played a central role in Canada becoming a nation. If one

believes the some media pundits, this century-old view, actively

promoted by the present federal government is unfounded. True,

unbridled Canadian patriotism of the late 1800s distorted some

facts and embellished the roles of some individuals from the

war. But who could blame them? Charting a path separate from

the United States had required an independent national

identity. The heroes of the War of 1812 were the perfect

solution.

Patriotic

books, poems, plays, and monuments were produced to honour the

heroism of Sir Isaac Brock, Tecumseh, Laura Secord and

Charles-Michel de Salaberry. They were all held up as role

models for Canadians to follow. This resonates in our national

fabric even today. To women activists, Secord was even more

important. While fighting for women’s right to attend

university and vote, Journalist Sarah Anne Curzon was taken by

Secord’s strength of character. Who wasn’t?

After all in

1860, eighty-five year old Secord bravely challenged the male

establishment and made sure she was counted among the veterans

of 1812. Travelling by cart, she had shown up at a clerk’s

office in Niagara-on-the-lake to sign, with other veterans, a

message to the visiting Prince of Wales (future King Edward

VII). Initially resistive, the clerk was put in his place by

the determined Secord and her signature was allowed. The local

newspaper supported her action and the Prince was so taken by

her gesture that, upon his return to England, a sizeable sum of

money of granted to Secord for her wartime service.

Curzon wrote

extensively about Secord throughout the closing decades of the

19th century. Her point in doing so was to show

that Canadian women had also patriotically served Canada in

1812, and that women were just as qualified as men to be

historians. Curzon’s interest in the war continued to grow

and in 1890 she called for “the erection of a monument for the

heroes of the War of 1812.”

Women's Rights Activist Sarah Anne

Curzon championed female access to a University education.

Her daughter would become one of the first women to graduate

from the University of Toronto

Until this

point, monuments in Canada had been confined to honouring

specific people, the most significant one being to Sir Isaac

Brock. The Canadian attachment to Brock was very real from the

start - not some fabrication or myth. Upon the war’s

conclusion, the Upper Canadian Parliament immediately approved

the building of a monument to their fallen

Lieutenant-Governor. A massive stone tower built on Queenston

Heights overlooking the Niagara River, Brock’s Monument soon

became a target for those wishing a republican path for Canada.

In 1840, a huge explosion of gunpowder at the base of the tower

broke the stillness of the majestic spot. It was Canada’s first

terrorist attack. However, unlike the World Trade Towers on

September 11, 2001, Brock’s tower monument did not collapse.

Still the structure was declared unsound.

The public

outcry was swift. Led by the Speaker of Upper Canada’s House of

Assembly, Allan Napier MacNab, a group of Canadians demanded the

tower be replaced with an even greater monument. Public

donations soon flowed in, principally from the militia and

native communities of the province. MacNab, a veteran of 1812

himself, continued to lead the reconstruction effort. In

Parliament, MacNab got passed Canada’s first anti-terrorism law

outlining punishments for anyone attempting to blow up the

monument again.

“The blood of our

militia and our valiant Indian allies was freely

shed, and mingled with the blood of the regular

soldiers with whom they fought and died side by side

in the defence of Canada… Every drop of blood shed,

every life lost in that eventful struggle, did but

cement more strongly attachment to the soil and

fidelity to the Crown…” – Allan Napier MacNab,

Premier of Canada, 1859.

While Premier

of Canada (1854-6), MacNab expanded his view on why the new

Brock Monument was being constructed. In 1859, thousands

listened as MacNab inaugurated the monument to the memory of

Brock, and “those who fell by his side upon the battlefield, and

through them to the imperishable memory of all who fell in

defence of Canada.” In essence he wanted people to consider the

monument an “emblem of a nation’s gratitude” to all 1812

Veterans. De Salaberry’s son was present, further underlining

MacNab’s intent. While MacNab said it was “one of the proudest

and happiest days of my life”, his more inclusive view did not

stick. Canadians viewed it solely as a monument to Brock.

Did the

Canadian government really have a responsibility to 1812

veterans? Yes. After Confederation in 1867, the Dominion of

Canada assumed responsibility of 1812 veteran pensions from the

provinces. This responsibility was expanded by a Liberal

Government in 1877 when pensions were extended to all 1812

veterans, not just those who had been wounded. So how Canada

treats its veterans today is very much connected to its historic

responsibilities towards the veterans of 1812.

Canadian

attempts to recognize 1812 veterans in other ways created a

string of failures. During the war itself, the Loyal and

Patriotic Society of Upper Canada was established to provide

warm clothing to the troops, and help the widows and orphans of

dead militiamen. After the war, with the government covering

pensions to widows, the charity focussed itself on producing the

“Upper Canada Preserved” medal for serving militiamen. However

not enough medals could be made to meet the demand so they were

never issued. In a controversial move, all the medals

manufactured were defaced and sold as bullion in 1840. Proceeds

from the sale went to the Toronto General Hospital. While a

worthy cause, the hospital was not why many Canadians had

donated to the charity.

After decades

of waiting, a medal was issued in 1847 by the British Parliament

for its veterans and to a small fraction of those who had served

in the Canadian militia. Although generous, the medal had not

come from those who had benefitted the most by the veteran’s

service: the Canadian people. As time rolled on, Canada’s

veterans from North West Rebellions in 1885 and the South

African War were granted pensions and honoured with monuments

for their efforts and sacrifice. However by the turn of the 20th

century, Canada was still without a national monument to 1812

veterans. Considering more Canadians died in 1812-15 than in

Afghanistan, Korea, South Africa and in the North West

combined, the omission was glaring. With Canadian

communities put to the torched, and parts of the population made refugees

in 1812, the civilian sacrifice alone justified such an

endeavour.

In 1902, the

Army and Navy Veterans Association tried to pay this

commemorative deficit by building a monument to 1812 soldiers

interred at the old Military Burying Ground outside Fort York in

Toronto. Because most of the graves were unmarked, the

monument served both as a testament to local 1812 veterans and a

sort of grave marker. Completed in 1907, the monument was

almost immediately forgotten about. Its location was far from

other military monuments at Queen’s Park and therefore was left

out of celebratory events for veterans. A century earlier,

Brock himself had identified the necessity of placing a monument

near where “constant bustle reigns.” The spot he picked for

the Nelson pillar in Montreal is still today a place where

multitudes assemble.

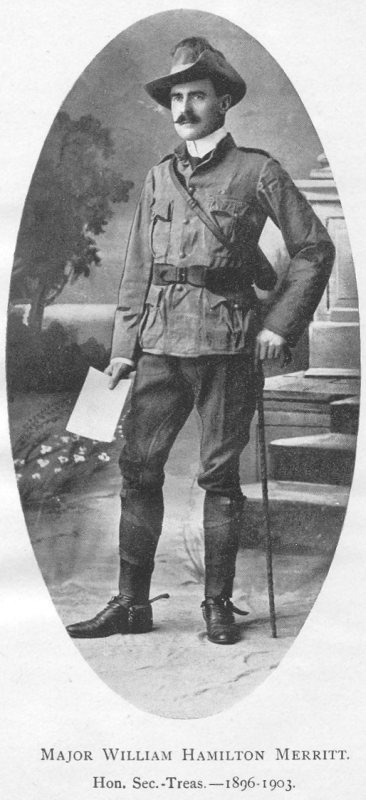

Another attempt

at a national monument for 1812 was not long in coming. Before

Veterans ceremonies in Toronto on May 25, 1909

Lieutenant-Colonel William Hamilton Merritt announced the idea.

To him, an 1812 national memorial was needed at the Ontario’s

legislature to commemorate “the brave men who saved Canada in

1812 to 1814 and who laid deep and strong the foundation stone

of this great Dominion.” Obviously the Harper Government’s

claim that “the War of 1812 was a seminal event in the making of

our great country” is hardly new. Surprisingly Merritt was

unaware that an 1812 monument had been completed two years

earlier in Toronto. This speaks to the limited success of that

endeavour.

A

monument is needed to “the brave men who saved

Canada in 1812 to 1814 and who laid deep and strong

the foundation stone of this great Dominion.” -

Lieutenant-Colonel William Hamilton Merritt, 1909

"The War

of 1812 was a seminal event in the making of our

great country ... Events surrounding the

1812-15 armed conflict laid the foundation for

Confederation and established the cornerstones of

many of our political institutions." -Prime Minister

Stephen Harper, 2012

With

encouragement from Ontario’s Premier -but no money- Merritt

moved forward with his idea as a way to mark the war’s

centennial. With grandiose plans, Merritt petitioned the

federal government for financial support in 1912. This drew

criticism from the Ottawa Citizen who deemed Toronto as

an inappropriate location for such a monument. Still confident

things would work out, French sculptor Paul Chevré was asked to

submit a design for the War of 1812 monument. Eerily

foreshadowing events to come, Chevré chose the Titanic as

his means of transportation to North America to present his

ideas. While he survived the ocean liner’s sinking, the plans

for the monument shared the same watery fate as the war’s

veterans off Newfoundland in 1816.

With no plans

and little money, the monument project was sunk. To salvage the

situation, Merritt asked Prime Minister Robert Borden for

permission to mount a simple plaque in Parliament’s centre block

in Ottawa, commemorating the battles of the War of 1812.

Unveiled in 1913, this plaque survived the fire of 1916 that

destroyed the building and is still on a wall in Parliament

today. Unfortunately, like Toronto’s monument near Fort York,

few are even aware of its existence.

For the next

century Canada focussed its commemorative efforts on

designating, marking, preserving and in some cases

reconstructing War of 1812 historic sites of national

significance. Scholars turned their attention to de-bunking

myths and distortions of facts about the War of 1812. In doing

so, however, the word “myth” became associated with the role of

Canadians in the war. The principal 1812 myth that was

dismantled was that farmers with no military training had won

the war. This was untrue. But trained Canadian regulars

(including full-time Canadian militiamen), with their native

allies, did play a central role in the conflict’s outcome.

Though called

for by generations of Canadians before World War One, the idea

of an 1812 national monument was washed away by the waves of

commemorative projects for the conflicts of the 20th

century. Luckily over time our national consciousness seems to

strive for equity and balance in commemorative efforts.

Therefore in 2012 when the Canadian Government announced a

National War of 1812 monument for Parliament Hill, scholars

should not have been surprised. It is an outstanding debt the

Canadian people have borne for two centuries.

During the

World Wars, the name of De Salaberry and “les héros de

Chateauguay” were referred to often in military recruiting

drives in Quebec. He was Quebec’s most popular war hero and

had been recognized as such by the province’s Legislature in

1814. It seems only fitting that a statue of him, along with

other prominent historical figures, was included in designs of

Quebec’s National Assembly in 1886. It was these statues that

inspired Quebec’s motto “Je me souviens” or “I remember.”

But some

Canadians have clearly forgotten the central role 1812 played in

the development of our national identity. In MacLean’s

Magazine on March 20, 2013, John Geddes opined the proposed

monument was inappropriate for Parliament Hill, especially at

its proposed location overlooking the National War Memorial.

On the contrary, it is exactly the right spot.

Borden’s

decision in 1913 to allow Merritt’s plaque on a wall in

Parliament does establish a precedent for 1812 on the Hill. The

presence of military monuments and figures at both Ontario’s and

Quebec’s legislatures offer further weight to this argument.

With the Canadian Forces perpetuating units from the War of

1812, locating the monument close to the National War Memorial

is ideal. By doing so, the new monument can be included in

remembrance events. Keeping the memory alive of the sacrifice

of 1812 veterans is the point.

The Duke of

Wellington fought at the time of the War of 1812, and placing

the monument beside a street named after him appears

appropriate. It is a memorial to troops he trained and fought

with, as well as to Canadian combatants. The monument being

near the Rideau Canal is also noteworthy. The war had made

officials realize the necessity of building the canal system.

Without the canal there would have been no Ottawa to select as

Canada’s national capital. Let us not forget that many of

the elements of the Parliament buildings, like the Peace tower

and the Memorial Chamber, are to honour our soldier's

sacrifices.

In 1812,

provincial parliaments created military units that fought and

died defending Canada. The Parliament of Canada inherited that

legacy in 1867 when it recognized its legislative responsibility to 1812

veterans. For 200 years, Canadian legislators have sent troops

to fight Canada's battles. It is requisite Members of Parliament are

constantly reminded of the ultimate sacrifice Canadians have

made in following their orders. The 1812 monument is not only

suitable for Parliament Hill, it is long overdue.

|

Canadian Premier Sir Allan

MacNab: Veteran and 1812 Advocate

The party Sir John A. Macdonald

would eventually lead was born in 1854. That year

Augustin-Nobert Morin’s parti bleu in Canada East

and Canada West’s Conservatives lead by Sir Allan

Napier MacNab had joined forces and won control of

the Legislative Assembly of the united Province of

Canada.

Though Morin’s father was a

Captain in the Saint-Hyacinthe Militia and had been

called up during the American invasion of Lower

Canada in November 1812, it is Premier MacNab’s 1812

war record that is most noteworthy (a conflict

MacNab in 1815 called “the War in Canada”). When

the American fleet arrived to attack the provincial

capital of York (Toronto) on April 27, 1813

fifteen-year-old MacNab was busy with his studies at

the Home District School (corner of King and George

Streets) Able to bear a musket, he and some of his

classmates were called upon to defend the town.

Whether MacNab was actually engaged against the

invaders is unknown. With the town overrun, MacNab

morphed from soldier to refugee.

Retreating with the surviving

troops eastward towards Kingston, MacNab trudged

through the cold rain “pouring in torrents” making

the road almost impassable. With only the soaking

clothes on his back and little to eat, MacNab’s

first military experience was hardly glorious.

After finally arriving in Kingston, military

officials were stuck with the problem of figuring

out what to do with the young MacNab.

MacNab’s father had been a

lieutenant in the Dragoons of the Queen’s Rangers in

the American Revolution, and was known to

Lieutenant-Governor Major-General Sir Roger Sheaffe.

(his father would also serve as Usher of the Black

Rod for the provincial legislature from 1815 to

1830). As a result a midshipman’s position the HMS

Wolfe was arranged for MacNab. A month later, the

lake fleet set sail with the young adventurer to

attack the American naval base at Sackets Harbor,

New York. Discouraged by the unlikelihood of

gaining an officer commission in the Royal Navy,

MacNab turned his attention to the army.

Willing to earn a commission,

MacNab was appointed to the British 100th

Regiment of Foot as a gentleman volunteer. This

meant he trained, marched and fought with the rank

and file, but dined and socialized with the

officers. If MacNab could prove himself a worthy

soldier, an officer’s commission was in the

offering.

When MacNab and his regiment

marched into his birthplace of Niagara-on-the-lake

in December 1813, the Upper Canadian town was a

smoldering ruin. The Americans had burnt the

community and withdrawn across the river to winter

quarters in Fort Niagara and Buffalo, New York.

However a settling of accounts was close at hand.

Under the cover of darkness, MacNab and 100th

Foot crossed the river and stormed Fort Niagara,

capturing the American garrison. His commanding

officer was quick to single out MacNab for his

“great bravery and zeal” in being “amongst the

foremost during the attack of the picquets and the

assault of the works.” MacNab finished the month by

participating in the attacks on both Black Rock and

Buffalo.

The next month,

Governor-General Sir George Prevost awarded MacNab’s

valour by recommending him for a commission in Sir

Isaac Brock’s old regiment, the 49th

Foot. With a gold epaulet on his shoulder marking

his rank as an Ensign in his new regiment, MacNab

participated in the campaign against Plattsburgh,

New York in 1814.

It is interesting to note that

41 years later in 1855, Morin would be replaced as

MacNab’s governing partner by another veteran of the

Plattsburgh campaign, Étienne-Paschal Taché.

Together, these two War of 1812 veterans led the

Province of Canada and passed sweeping changes to

the Militia. The effects of the Militia Act of

1855 can still be seen in the Canadian Army today

and Taché is recognized as the Department of

National Defence's first Minister. It seems

only fitting that Taché 's son would author Quebec's

motto "Je me souviens" or "I remember".

Alas it was a short-lived

partnership. Distracted by railroad interests and

slow to appease growing discontentment within the

new party, MacNab was forced aside to make way for a

new leader, John A. Macdonald.

Today MacNab’s home, Dundurn

Castle, is a National Historic Site and can be

visited in Hamilton, Ontario. It is only fitting

that local artefacts of the War of 1812 are also on

display there as part of the Hamilton Military

Museum.

|

|