The American Attack at Frenchtown

on the River Raisin, January 18, 1813

by Robert Henderson

Village

of Frenchtown on the River Raisin looking north (National

Parks Service)

When two residents of

Frenchtown (modern day Monroe, Michigan) arrived on January

13, 1813, American Brigadier-General James Winchester was

busy directing his men to gather provisions from abandoned

corn fields around his camp. Pounding devices were already

set up to turn the parched corn to meal for baking.[1]

It was with some relief that his men worked. After spending

months plagued with disease and hunger while encamped at

Fort Defiance in Ohio, the snow-covered shores of the Maumee

River proved better suited for the health Winchester’s

advance force of a thousand soldiers. The supply of new

clothing from Kentucky had also helped. However another

danger had increased. A skirmish with native warriors two

days previously had awoken the enemy in the region to their

presence.[2]

With the help of a

translator, the francophone settlers from Frenchtown painted

Winchester a bleak picture of the situation in their

community. After the surrender of Detroit, Frenchtown had

become an advance post for the British and Canadian militia

were frequently stationed there.[3]

Situated on the banks of the River Raisin where it joins

with the Lake Erie, Frenchtown was aptly called since it was

populated primarily by unilingual French Canadians. It was

an awkward situation for Frenchtown’s residents. They were

American citizens in a territory controlled by the British,

and surrounded by native settlements allied with Tecumseh

against the United States. They also had family and

cultural connections with the settlers on the Canadian

shores of the Detroit River. Stripping away conflicting

nationalities, often the principle concern of most settlers

on the frontier was for the preservation of their lives and

property. While some took up arms for the United States,

many stayed neutral.

On January 16, another

resident arrived at the American camp reporting that

Frenchtown was about to be destroyed by the two flank

companies of Canadian militia stationed there. This fear

was unjustified. The day Winchester first met with the

settlers on the 13th, the British commander of the occupied

territory, Colonel Henry Proctor, wrote to his superior

about his desire to protect the neutrality of Michigan

territory’s residents:

Mature reflection on the reading within

my reach had determined one against demanding the military

service of the inhabitants of the ceded Territory. I dread

the consequences of their account solely, of the enemy

entering into the Territory. No commands or influence of

mine will be of sufficient weight to preserve the property

and I doubt the lives of most of the inhabitants, in the

event of it.[4]

In addition Proctor recommended

immediately attacking Winchester on the Maumee River. No

plan to destroy Frenchtown was being contemplated. However

whether real or imagined, the report from his visitors from

River Raisin had provided Winchester with a reason to

advance and engage the enemy.

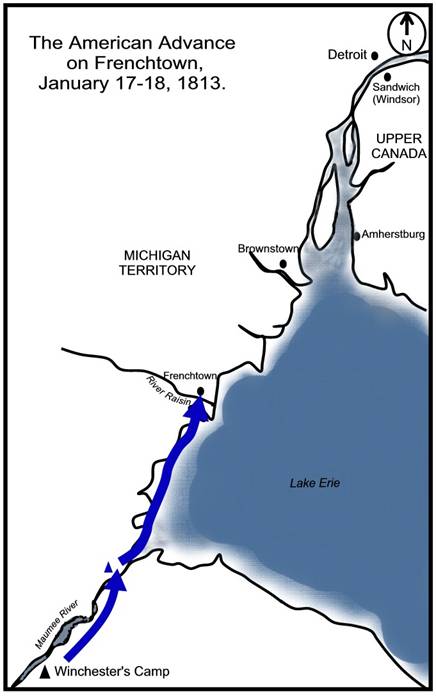

Map of Region (R. Henderson)

While his superior

Major-General William Harrison had ordered him to wait for

reinforcements, Winchester felt the distance between him and

Harrison allowed him to act as an independent command.

Permitting commanders to make decisions in the field without

being micromanaged from afar is an important element to

successfully waging a war. However Winchester’s decision

was coloured by his competition with Harrison for overall

command in the Western theatre. Sixty-year-old Winchester

felt he was the better candidate for the job because of his

service in the American Revolution and that he held a

Brigadier-General’s commission in the regular Army. The

fact he was captured twice by the British in the

Revolutionary War seemed not to have affected the impression

of him being a seasoned and successful veteran. In the

end, popularity forced the hand of the government in

Washington. Kentuckians wanted Harrison and viewed

Winchester as somewhat of a dainty, who had little in common

with the average frontiersmen that he wished to lead into

battle. After all Winchester was the first in his community

(to become Memphis, Tennessee) to install a ballroom in this

house.[5]

Brigadier-General James Winchester, 1817 (Historic Craigfont

Mansion)

After a war council with his

senior officers, Winchester ordered 570 Kentucky Volunteers

of the 1st and 5th Regiments, under the command of Colonel

William Lewis, to capture Frenchtown from the Canadians.

After crossing the Maumee River, Lewis had his men set up

camp. That night an additional 110 men of the 1st Rifle

Regiment of Kentucky Volunteers under Lt Col John Allen[6]

caught up with Lewis and joined the expedition.

Conflicting reports flowed in about enemy troop

movements. One suggested that the Canadian militia and

Natives had pulled back out of Frenchtown and were eighteen

miles north at Brownstown. Another suggested a relief force

from the Canadian side of the Detroit River was preparing to

cross the ice and move towards River Raisin. Neither were

true. Early the following morning Lewis broke camp and

hurried his force forward using the frozen coast line of

Lake Erie as a road. “We proceeded on with no other view

than to conquer or die” noted one Kentuckian.[7]

Waiting for the arrival of

the Americans was fifty men of the Essex Militia,

[8] under the command of Major

Ebenezer Reynolds, and anywhere from one to two hundred

Potawatomi warriors.[9]

Born in Detroit, Reynolds had moved across the river with

his family to the Canadian garrison town of Amherstburg when

Michigan was handed over to American control in 1794. His

father, Thomas Reynolds was the local fort’s commissary

until his death in 1810 and Ebenezer had taken up residence

further west in Colchester before joining the Essex

Militia. On January 18 Major Reynolds also had at his

disposal a small 3-pdr artillery piece manned by militia

volunteers, under the direction of Royal Artillery

Bombardier Kitson. The sole British soldier present, Kitson

had trained the Canadians well in the quick operation of the

3-pdr. Stationed there since November 1812,[10]

the Essex Militia had become quite familiar with the village

and the surrounding area.[11]

At Reynolds side was Adjutant

William Duff. In the first months of the war Duff had seen

action in three engagements: Brownstown, Maguaga and the

taking of Detroit.[12]

At the Battle of Maguaga, some of the Essex militiamen

present adopted not only native warfare tactics, but also

their attire.[13]

Unfortunately, however experienced some of his men had

become in the war, Reynolds was short on troops. Both

Captain William Elliott’s (1st Essex) and Captain Alexis

Maisonville’s (2nd Essex) flank companies had only 25

effectives present. These two flank companies were well

suited for interacting with the local population since they

were almost entirely composed of French Canadians. Only

Elliott’s company had a sprinkling of Anglophones in it.[14]

Trying to keep warm in his hemp linen tent[15]

was Ensign Joseph Eberts from Maisonville’s Company. An

employee of the North West Company, Eberts had lost almost

everything when his house was pillaged by invading American

troops in July 1812 near Sandwich, Upper Canada. In charge

of NWCo. trade in the Wabash area, Joseph had a good working

relationship with the native allies present at River

Raisin. With him on that cold day was his fifteen-year-old

brother William Henry, who was serving as a private in

Maisonville’s Company.[16]

French Canadian

Militiaman, 1813 by G.A. Embleton (Parks Canada)

Dressed in white winter

capots, the Essex Militia looked no different from most of

the local population, except that their blanket coat hoods

were edged with black.[17]

Ordered the previous month, the addition of the black edging

was critical in helping native allies differentiate between

friend and foe during chaotic bush fighting. Their

knee-high moccasins gave the Essex men both warmth and good

footing on the ice and snow. While most of the French

Canadians wore tuques, Anglophones like Reynolds seemed to

have had a preference for fur caps. The officers dressed in

civilian attire like the men. One description of a local

Canadian militia officer in 1812 noted his “rank as an

officer was only distinguishable from the cockade

surmounting his round hat, and an ornamented dagger thrust

into a red morocco belt encircling his waist.”[18]

Being at the end of the supply line, standard military dress

was slow in coming for the militia. However on that January

day the Essex Militia’s winter attire offered a degree of

uniformity and camouflage against the snow. The flank

companies were armed with the standard 3rd model brown bess

and had infantry accoutrements, although captured American

arms and equipment may have been issued to some.

Word quickly arrived of the

American column approaching from the south and Major

Reynolds set about positioning his men behind the houses and

fences of the village. Natives likewise positioned

themselves behind cover, although fighting in such an open

space was not conducive to their method of warfare. For his

part, Bombardier Kitson ensured his 3-pdr gun had a clear

view of the southern shore of the River Raisin from behind a

picket embrasure.[19]

Frozen solid, the river would provide little deterrent to an

advancing enemy. Outnumbered four to one, the little force

at Frenchtown would need a brilliant stroke of luck to

successfully defend their post.

At 3:00pm the Kentuckians

appeared. As Colonel Lewis formed his three regiments into

line, Kitson’s artillery piece opened fired. Dividing into

three, the American line began crossing the frozen River

Raisin. The ice proved tedious and the men slipped and

slided trying desperately to gain surer footing.[20]

The slow advance gained speed after Lewis ordered his troops

to ditch their cumbersome knapsacks. Mocked by the

Americans as “large enough to kill a mouse”, Kitson’s small-calibre

artillery piece popped away without effect. When they

reached the other side of the River Raisin one Kentuckian

remembered the troops around him “raised a yell, some

crowing like chicken cocks, some barking like dogs, and

others calling ‘Fire away with your mouse cannon again’”.[21]

Ordered to close with the

enemy, the 1st and 5th Infantry Regiments of Kentucky

Volunteers, making up the left and centre of the line,

advanced “under an incessant shower of bullets”. Both

Battalions quickly moved to outflank and dislodge Reynolds

men from the security of the village. Leading the advance

was Captain Bland Williams Ballard, who had a reputation as

a fierce native fighter. Allen’s Riflemen, composing the

right of the line quickly join the push. Endangered of

being encircled, the Essex Militia and natives pulled back

out of Frenchtown and darted across the open fields to the

edge of the forest to the north and reformed. A Kentucky

rifleman described the advantageous spot Reynolds had

positioned his men: “after pursuing them to the woods, they

made a stand with their [artillery piece] and small arms,

covered by a chain of enclosed lots and a group of houses,

having in their rear a thick brushy wood filled with fallen

timber.”[22]

At the

age of 53, Captain Bland Ballard was the most experienced

that day

at fighting native warriors and lead the advance “great

skill and bravery.”

To this point, American

casualties had been light. This would soon change. While

the Essex Militia concentrated their fire on Allen’s

Riflemen, the Kentucky Infantry moved along the edge of the

woods to press the Canadian right flank. With the Americans

pressing forward and on the side, Reynolds wisely pulled his

men back from the fences and into the woods, joining the

native warriors there. Throughout this the natives kept

up a brisk and effective fire on the 1st Kentucky Rifle

Regiment, forcing Allen at one point to partially retreat

while the other Regiments attacked the flank.[23]

However the American pursuit did not end. One Kentuckian

remarked how when they “reached the woods the fighting

became general and most obstinate, the enemy resisting every

inch of ground as they were compelled to fall back.”[24]

Reynolds brother commented later how the Essex Militia

“fought most bravely, retired slowly from log to log.”[25]

Captain John McCalla of the 5th Infantry Regiment of

Kentucky Volunteers was taken aback by the intensity of the

fighting witnessing “my fellow soldiers extended lifeless

bloody corpses on the ground, and many others crying in

agony from dangerous wounds. I have heard balls whistling as

thick as the pattering hail, around me and yet not touched,

even in my clothes. I wondered that I should escape, and

expected every ball would be for me.”[26]

Kentucky Rifleman William

Atherton concurred stating “the fight now became very close,

and extremely hot ... I received a wound in my right

shoulder.” The moment before Atherton was hit he witnessed

two of his fellow riflemen move too far forward. One was

killed and the other wounded.[27]

Atherton also recounted seeing “several of our brave boys

lying upon the snow wallowing in the agonies of death.”[28]

The native warriors and the Essex Militia showed themselves

expert in bush warfare. Atherton described perfectly the

bash-and-dash tactics being used by Reynolds: “Their method

was to retreat rapidly until they were out of sight (which

was soon the case in the brushy woods) and while we were

advancing they were preparing to give us another fire; so we

were generally under the necessity of firing upon them as

they were retreating.” Another Kentucky private had similar

recollections: “As we advanced they were firing themselves

behind logs, trees, etc. to the best advantage.”[29]

For two miles through dense

woods Reynolds’ force kept battling the Kentuckians, who

charged each of the positions set up by the Essex militia.

Only the setting of the sun brought the running battle to a

close. In total the battle had lasted three and a half

hours. Leaving the dead and pulling back to encamp at

Frenchtown, the American tallied their losses. The bitter

fighting had resulted in twelve killed and 55 wounded.

Among the wounded was Frenchtown resident Antoine Mominie.

Mominie had broken his parole, or promise not to fight until

officially exchanged, and had attached himself with the

Kentucky riflemen. Suffering a debilitating wound in the

battle, Mominie would later be denied an invalid’s pension

from the U.S. Treasury.[30]

To them, he was technically a prisoner of war on parole and

therefore a non-combatant. Despite the casualties, the

Kentuckians took pride in how they handled themselves in the

battle. While some died, they had conquered.

The number of Canadian and

aboriginal casualties is unfortunately unknown. A native

and two Canadians were taken prisoner and one witness noted

“from the number found on the field where the battle

commenced, and from the blood and trails were they had

dragged off their dead and wounded, the slaughter must have

been considerable.”[31]

Strangely surviving muster rolls of the Essex Militia make

no mention of any casualties during the battle.[32]

Determining the number of native casualties is unfortunately

next to impossible.

Reynolds and his exhausted

men trudged north along Hull’s road through the night,

eventually arriving at the Wyandot village of Brownstown on

the Huron River. From there, a scout was dispatched across

to Canada to warn Colonel Proctor that Winchester’s advance

force had taken Frenchtown. The news arrived at 2:00am in

Amherstburg while the officers of the garrison were in the

middle of celebrating the birthday of Queen Charlotte at a

ball. The ball had been arranged by “les jeunes de gens de

la cote” or the young French Canadians of the coast for the

military. Little did they know that while they were

merry-making, their friends and family were locked in a

desperate struggle with the enemy in the woods of Michigan.

The music came to an abrupt halt when a British officer

barged in announcing: “My boys you must prepare to dance to

a different tune; the enemy is upon us and we are going to

surprise them.”[33]

In the coming days Proctor would gather together all his

forces, cross the ice and rendezvous the Reynolds men, and

then take the war back to Frenchtown.

French Canadian Round Dance in winter time, 1801 (Library

and Archives Canada)

Postscript

In the United

States the skirmish with the Essex Militia and natives on

January 18 has become known as the first battle of the River

Raisin. Surprisingly, considering its ferocity, the

engagement is hardly mentioned in Canadian history texts of

the war. Not having British officers present to report on

events likely contributed to the overlooking of the noble

efforts of the Essex Militia. Upon conclusion of the

campaign, Proctor’s official dispatch of events was somewhat

vague on the January 18 engagement. He stated being

informed on January 19 that the enemy was

...in possession of Frenchtown on the

River Raisin, 26 miles from Detroit after experiencing every

resistance that Major Reynolds of the Essex Militia had it

in his power to make with a three pounder well served by

Bombadier Kitson and the Militia men whom he had well

trained to the use of it. The retreat of the Gun was

covered by a brave band of Indians who made the enemy pay

dearly for what he obtained.[34]

During the second battle of

Frenchtown (River Raisin) on January 22, 1813 the Essex

Militia again played an important role, though somewhat

overshadowed by the efforts of the 41st Regiment of Foot and

the Royal Newfoundland Fencibles. Later on May 5, 1813 the

Essex Militia would clash with the Americans at the Battle

of Maumee and Reynolds was again in the thick of it. Even

with Essex County under enemy occupation in 1814, men from

the flank companies - as the Loyal Essex Volunteers or

Rangers - continued the fight in the Niagara peninsula,

suffering casualties at both the battles of Chippewa and

Lundy’s Lane. It was at the former battle, that Ensign

Joseph Eberts of the 2nd Essex Regiment lost his younger

brother William Henry. Records of war losses suggest the

Americans occupying Essex County were harsh on the families

who had men fighting “for their country.”[35]

For example, Joseph Eberts house was destroyed and his wife

with their two young children (aged one and three) were

turned out in the cold at the end of 1813.[36]

Today the Essex Militia

Regiments are perpetuated by the Essex and Kent Scottish, a

Primary Reserve Regiment in the Canadian Army. In 2012 the

Essex Militia was rightly awarded the honours ‘Defence of

Canada, 1812-15’, ‘Detroit’, ‘Maumee’ and

‘Niagara’. Their service record in the war more than

justifies these honours and it is only unfortunate it took

so long for them to be awarded. It is to be hoped that

further research will be done on both the Essex Regiments in

the war and the challenges faced by the residents of Essex

County during the American occupation of 1813-1814.

Members of the Essex and Kent Scottish in wintertime (Unit

Website)